The North African Campaign, or the War in North Africa (June 10, 1940 – May 13, 1943) – military operations between the Anglo-American and Italian-German troops in North Africa – on the territory of Egypt and the Maghreb during World War II.

The fighting in sub- Saharan Africa – in East, West and Central Africa are considered separately in the article ” African Theater of Operations “. On the territory of Tropical Africa, hostilities were conducted separately from the North African campaign – by the allied forces against the Italian troops (Ethiopia, Djibouti, Eritrea and Somalia), and against the French troops of the Vichy government (Gabon, Senegal, Chad, Madagascar, Reunion)

In September 1940 – October 1942 in North Africa, the fighting went on with varying degrees of success. On October 23, 1942, General Montgomery ‘s 8th British Army went on the offensive, breaking through the front of the Italo-German troops near El Alamein. At the same time, American troops under the command of General Eisenhower landed in Casablanca (Morocco) and Algiers (Algiers). Italo-German troops were driven back to Tunisia and capitulated on the Beaune Peninsula on May 13, 1943.

Background to the conflict

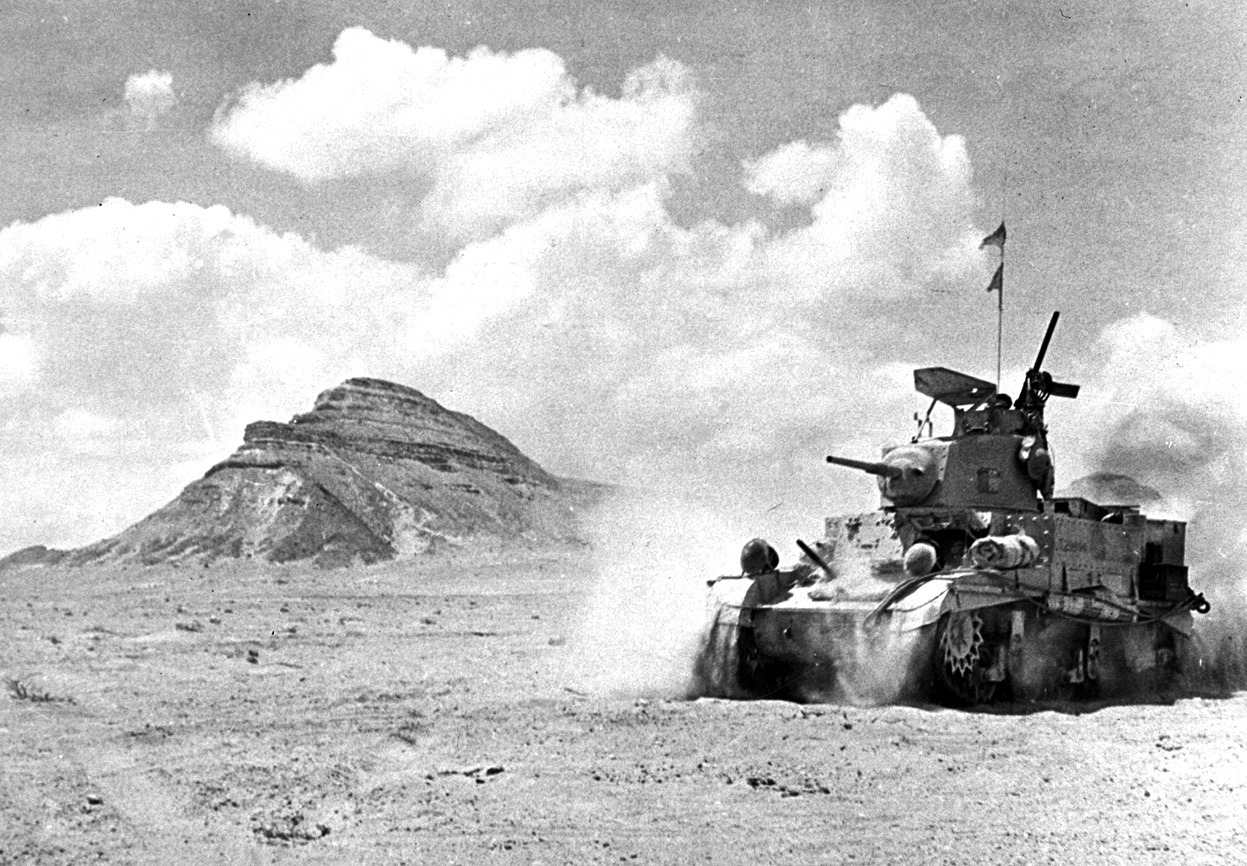

M3Lee North Africa

By the beginning of the Second World War, the rivalry of the colonial powers for dominance in North Africa had not ceased for at least a century and a half. The strategic role that this region could play in the event of a European or global conflict could not be discounted. Despite the fact that North Africa practically did not have any natural resources necessary for waging a modern war (Libyan oil had not yet been found), it was of great strategic importance: the side that had its military bases there was able to “block” and water, and overland routes to India, Malaya, as well as to the British dominions – Australia and New Zealand. The same can be said about the routes connecting the Black Sea ports with the Mediterranean Sea and the Atlantic. In the interwar years, the role of oil fields discovered and operated by British companies in Iraq and Iran began to rapidly increase. Since the disputes between England and France over the colonies subsided at the beginning of the 20th century, until the 1930s, nothing threatened the sea route to India and other colonies.

But in 1935, Italy decided to seize Ethiopia, using its bases in Eritrea and Italian Somalia to achieve this goal. A year later, Italy successfully took possession of this country, and as a result of Great Britain’s communication, a significant segment of the sea route to India was under possible attack. In addition, Italy had naval and air bases in the Mediterranean zone – in Libya, in the south of the Apennine Peninsula, as well as on Rhodes and other islands of the Dodecanese archipelago. During the Spanish Civil War in 19361939 _ Italian armed forces settled in the Balearic Islands.

Thus, by 1940, the conflict was already well overdue, and both sides felt quite confident in northeast Africa, although each in its own way. The British had a system of bases guarding the shipping route to India and the oil-bearing regions of the Middle East. And the Italians, thanks to the fact that this sea route passed here, could already cut it at any moment, and not in one, but in several places.

Balance of Power

Italian troops

There were two armies in North Africa: the 5th Army, led by General Italo Gariboldi (eight Italian divisions and one Libyan) and the 10th Army stationed in Eastern Cyrenaica, led by General Guidi (one Libyan and four Italian divisions, of which two are blackshirts). The total number of troops was: 236 thousand people, 1800 guns and 315 aircraft. The commander-in-chief of this grouping was Marshal Italo Balbo, the governor-general of Libya. The technical backwardness of the Italian economy in many areas also affected the army. Almost all types of tanks and armored vehicles with which it was equipped were inferior to British tanks and armored vehicles in terms of speed, armament and armor quality.

British troops

By June 10, 1940, British troops, including parts of the dominions and colonies, were dispersed over a large territory: 66,000 in Egypt (including 30,000 Egyptians), 27,500 in Kenya, and about 1,500 – in British Somalia, 2.5 thousand – in Aden. The troops stationed in Sudan, Somalia and Kenya did not have tanks or anti-tank artillery. The air force of England, which had 168 aircraft in Egypt and Palestine, and only 85 aircraft in Aden, Kenya and Sudan, was significantly inferior to Italian aviation. The commander-in-chief of British forces in the Middle East was General Archibald Percival Wavell.

Italian offensive (1940)

General Wavell adopted the tactic of harassing the enemy with counterattacks. In skirmishes on the border, the Italians lost 3,500 people killed, wounded and captured during the first three months of the war, and the British only 150. Marshal Balbo also died at the same time: on June 28, Italian anti-aircraft gunners mistakenly shot down the plane on which he was flying, which was landing in Tobruk. He was succeeded by Marshal Rodolfo Graziani.

Marshal Graziani’s troops moved east on 13 September. Parts of General O’Connor slowly retreated, yielding to the numerically superior enemy, but sought to inflict as much damage as possible on him with artillery fire. On September 16, Italian troops occupied Sidi Barrani and did not go further – they dug in and took up defenses, and thus completed their offensive. For the next two and a half months, they prepared to continue the offensive, and the British to counteroffensive.

However, the British forces continued to retreat and only stopped at Mersa Matruh. This created a gap of 130 kilometers (80 mi) between the belligerents. The British command avoided open battle, given the small number of their forces. Graziani suspended the offensive in anticipation of the outbreak of the Italo-Greek war, then to resume it in the direction of the Suez Canal. He believed that the British leadership would be distracted by events in Greece, weaken their attention to Egypt, which would allow Italian troops to capture the Suez Canal without much effort. The situation in Egypt has stabilized. After the capture of Sidi Barrani by the Italians, there were no active hostilities for almost three months.

The serious failures of Italy in the war she had undertaken against Greece could not but be reflected in her position in Africa. The situation in the Mediterranean has also changed for Italy.

“… It took only a few months,” notes Hitler’s Admiral Ruge, “ to expose to the whole world the military weakness and political instability of Italy. The negative consequences of this for the conduct of the war by the Axis powers were not long in coming.

Italy’s failures allowed the British command to take more effective measures to secure the Suez Canal. Wavell decided to attack, which he called in his order “a raid by large forces with a limited purpose. ” The British units were tasked with pushing the Italo-fascist troops out of Egypt and, if successful, pursuing them to Es-Sallum. Wavell’s headquarters did not plan any further advance.

First British offensive (December 1940 – February 1941)

Bren Carrier Africa

On the morning of December 9, 1940, a small British force supported by 72 guns attacked Nibeiwa from the front and diverted the attention of the Italian garrison. Meanwhile, elements of the 7th Armored Division passed through the undefended sector between Bir Safafi and Nibeiwa and attacked the Italian camp at Nibeiwa from the rear. The attack of the English troops took the Italian garrison by surprise. The Italian generals, seized with panic, could not organize proper resistance.

The morale of the Italian troops was so low that on December 16 they left Es-Sallum, Halfaya and the entire chain of forts they had built on the border of the Libyan plateau without a fight. The plan for the offensive of Graziani’s troops on the Nile Delta failed. In this setting, British losses were negligible.

By the beginning of 1941, British troops had made significant progress, and on January 22, 1941, Tobruk was taken. However, on February 10, 1941, the British headquarters issued an order to suspend the advance of troops at El Agheila.

The danger of complete displacement from North Africa for Italy was over, although she still lost all her colonies in East Africa.

However, the German command took a wait-and-see attitude towards Italy. Germany decided to take advantage of the weakening of the Italian forces in Libya in order to help them create a strategic foothold in North Africa, necessary in the future to capture all of Africa. In addition, the capture of Egypt and the Suez Canal was also in the interests of Germany.

During February 1941, German troops were transferred to Libya under the command of General Rommel. However, the British did not pay much attention to the transfer of a large contingent of German troops to Libya.

The hasty retreat of the Italian troops was halted in mid-February 1941. The Italo-German combined forces began to move back to El Agueila and on February 22 met with British troops stationed at El Agheila and on the eastern border of the Sirte desert.

Rommel’s first offensive (March-April 1941)

German intelligence has established that the British have only two armored brigades of the 2nd Armored Division near El Agheila, scattered on a wide front by separate detachments and separated from each other, and in the Benghazi area there are parts of the 9th Australian Division, which constituted the main British forces in Western Cyrenaica. The German command took advantage of such a favorable opportunity and on March 31 delivered a blow to the British, which turned out to be sudden. One armored brigade was taken by surprise and completely destroyed.

On the night of April 4, the Italo-German troops occupied Benghazi without a fight, and on April 10 they approached Tobruk, which was surrounded by them the next day. Attempts by the Italo-German troops to capture Tobruk on the move were not successful, and they had to send their main forces towards Egypt. On April 12, the troops entered Bardia, on April 15 they occupied Sidi Omar, Es-Sallum, the passage of Halfaya, the oasis of Jarabub. This is where their progress stopped.

In June 1941, the British command made an attempt to release Tobruk with large forces. However, Wavell’s headquarters failed to keep the plans of their commander-in-chief secret, and they became known to the enemy.

June 15, 1941 in the area of Es Sallum and Fort Ridotta Capuzzo, an attack by British troops began, who recaptured several settlements from the Germans. On the night of June 18, German tank units again occupied Sidi Omar. In this area, the offensive of the German troops was stopped. The Italo-German command had no reserves to continue the war in North Africa, since all the main forces of Germany were already concentrated to fight against the Soviet Union.

Second Allied offensive (November 1941)

On November 18, 1941, the British 8th Army launched its second offensive in Cyrenaica – Operation Crusader (Crusader), the purpose of which was to push Rommel back to Tripolitania. The British offensive stopped on December 31 in the El Agheila region (the border of Tripolitania and Cyrenaica).

On November 18, 1941, the British 8th Army launched its second offensive in Cyrenaica – Operation Crusader (Crusader), the purpose of which was to push Rommel back to Tripolitania. The British offensive stopped on December 31 in the El Agheila region (the border of Tripolitania and Cyrenaica).

Rommel’s second offensive (May-August 1942)

From May 26 to May 27, 1942, Rommel went on the offensive, attacking the British positions on the “Gazala Line” west of Tobruk, and broke through the British defenses. From May 26 to June 11, the troops of the Fighting France successfully defended the fort of Bir Hakeim south of Tobruk from superior enemy troops. On June 11, the French units, like the entire British 8th Army, were ordered to retreat to Egypt. On June 20, German-Italian troops captured Tobruk.

In July 1942, Rommel received serious reinforcements – the fortress division stationed in Crete was transformed on August 16 into a mechanized formation, the 164th Light Division “Africa” as part of the 125th (since 1943 – the mechanized regiment “Africa”), 382- th and 433rd mechanized regiments, 220th artillery regiment, 154th armored reconnaissance (since 1943 – 220th motorized) battalion and motorized support units.

On 1 July, the 8th Army stopped Rommel at El Alamein. Until 27 July, Rommel unsuccessfully tried to break through the Allied defenses. Nevertheless, Prime Minister Churchill decided to remove the British commander-in-chief in North Africa from his post. On 15 August, General Harold Alexander was appointed to replace General Claude Auchinleck. The 8th Army was led by General Montgomery.

From August 31 to September 5, Rommel resumed attacks in the Alam Halfa area near El Alamein, but Montgomery successfully repulsed them.

Third Allied offensive (October 1942 – May 1943)

Main articles: Second Battle of El Alamein and Tunisian Campaign

Burning German Panzer 3

On October 23, 1942, British troops under the command of General Montgomery went on the offensive against the Italo-German troops and broke through the enemy defenses in the El Alamein area in early November. On November 2, British troops broke through the enemy defenses, and the German-Italian Panzer Army “Africa” was forced to retreat under enemy attacks across Libya. During the pursuit, British troops occupied the city of Tobruk on November 13, El Agheila on November 27 , Tripoli on January 23, 1943, and in the 1st half of February approached the Maret line west of the Tunisian border with Libya.

On November 8, 1942, the American-British divisions under the command of General Eisenhower began landing in Algiers, Oran and Casablanca. By the end of November, Anglo-American troops occupied Morocco and Algeria, entered Tunisia and approached the cities of Bizerte and Tunisia. Pursued by the 8th British Army, the German-Italian troops stopped on February 15, 1943 only on the Maret line, located in Tunisia, 100 miles from the border with Libya. February 19 Rommel attacked American troops in the Kasserine Pass area, but the Allies repelled the attack, counterattacked, and by the end of February Rommel retreated, after which he was recalled to Germany, and Colonel General von Arnim took the post of commander of the Axis forces in North Africa. On March 21, 1943, Anglo-American troops launched an offensive from the south to the Maret line and from the west in the Maknasi region and broke through the defenses of the Italo-German troops, who retreated to the city of Tunis in early April. On May 7, the Allies captured the cities of Bizerte and Tunisia. May 13, 1943 Italian-German troops surrounded on the Bon Peninsula, (250 thousand people) capitulated. This figure was later called into question. “General Alexander’s headquarters, in a report to Eisenhower on May 12, reported that the number of prisoners since May 5 had reached 100,000 people. It was assumed that by the end of the fighting, the figure would increase to 130,000 people. A later report stated that the number of prisoners was 150,000 people. The English historian A. Taylor wrote: “The Allies took 130,000 prisoners, but in post-war reports this figure rose to 250,000 people.” In his book, V. I. Golovushkin writes:“Allied intelligence believed that the enemy had 150,000 soldiers, but did not take into account the rear units, the civil and military administration of Tripolitania, which also fled to Tunisia. Isn’t that where the figure of 250,000 people comes from? However, the headquarters of the Africa group, in a report to Rome on May 2, indicated the total number of Italo-German troops at 170-180,000 people. But this was before the start of heavy fighting in the last week of the campaign. Thus it is difficult to understand why the number of prisoners is one and a half times the number of German troops. Maybe someone just wanted to exaggerate the significance of this victory? In general, the occupation of North Africa by the Allies sharply worsened the already difficult strategic position of the Axis countries in the Mediterranean.

Results

- In connection with the defeat near El Alamein in 1942, the plans of the German command to block the Suez Canal and gain control over Middle Eastern oil were destroyed.

- After the liquidation of the German-Italian troops in North Africa, the invasion of the Anglo-American troops into Italy became inevitable.

- The defeat of the Italian troops in North Africa led to the strengthening of defeatism in Italy, the overthrow of the Mussolini regime and Italy’s withdrawal from the war.