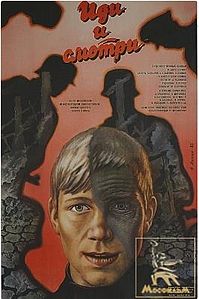

Come and See WW2 Movie History, Background, Reviews and Meaning:

“Come and See” (Belarusian: Idzi i look) is a Soviet two-part feature film directed by director Elem Klimov in the military drama genre according to a script written by him together with Ales Adamovich. Production of film studios ” Mosfilm ” and ” Belarusfilm “. The action takes place on the territory of Belarus in 1943. In the center of the plot is a Belarusian boy who witnesses the horrors of a Nazi punitive action, turning from a cheerful teenager into a gray-haired old man within two days.

Released in 1985 on the occasion of the fortieth anniversary of the Victory in the Great Patriotic War, the film won awards at several major film festivals and took sixth place in the Soviet film distribution in 1986 : 29.8 million viewers watched it. According to a poll of readers of the magazine “Soviet Screen”, was recognized as the best film of 1986, and subsequently strengthened in the ratings of the best films of various publications.

Plot

Belarus, 1943. A village teenager named Fleur (a diminutive of Florian), despite the protests of his mother, goes to the partisan detachment. There he meets a girl Glasha. Fleur is not taken into battle because of his young age, and he, offended, decides to leave the detachment. Some time later, the Germans begin a counter-partisan operation. The territory of the camp is under fire, German troops land on its location. Having miraculously survived, Fleur and Glasha are forced to flee the forest. Returning to Fleura’s native village, the teenagers do not find anyone there. Deciding that the inhabitants hid on an island in the middle of a swamp, Fleur and Glasha flee the village. At the same time, Fleura, unlike Glasha, does not notice that behind his house, near the wall, the recently shot villagers are lying. With difficulty reaching the island, teenagers find a group of residents who escaped from the Germans. Fleura learns that his mother and two young twin sisters have been killed. The shocked teenager, deciding that his departure to the partisans caused the death of his relatives, makes an attempt to commit suicide, but the inhabitants save him.

Peasants take turns spitting at Hitler’s effigy. At this time, Fleur is cut with a knife, and the cut hair, according to folk custom, is buried in the ground. Three armed peasants, together with Fleur, go in search of food for the civilians remaining on the island. Taken with them, they set up a effigy of Hitler at the crossroads. Not noticing the warning shield, two peasants are blown up by mines. At night, Fleur and his partner, a partisan nicknamed Frontier, come to the village and take away a cow from a local resident who works for the Germans. Tormented by hunger, they milk her in an open field, but they come under fire from the Germans, from which Frontier and the cow die. An exhausted teenager falls asleep right on the corpse of an animal. In the morning he tries to butcher the carcass and notices a cart with a horse passing by a peasant (Fleur wanted to load the meat onto the cart). At this time, a detachment of Germans landed in the field from armored vehicles and collaborators. The peasant persuades Fleur to hide the weapon in a heap of hay and go with him to the village under the guise of his grandson, Mitrofan.

Peasants take turns spitting at Hitler’s effigy. At this time, Fleur is cut with a knife, and the cut hair, according to folk custom, is buried in the ground. Three armed peasants, together with Fleur, go in search of food for the civilians remaining on the island. Taken with them, they set up a effigy of Hitler at the crossroads. Not noticing the warning shield, two peasants are blown up by mines. At night, Fleur and his partner, a partisan nicknamed Frontier, come to the village and take away a cow from a local resident who works for the Germans. Tormented by hunger, they milk her in an open field, but they come under fire from the Germans, from which Frontier and the cow die. An exhausted teenager falls asleep right on the corpse of an animal. In the morning he tries to butcher the carcass and notices a cart with a horse passing by a peasant (Fleur wanted to load the meat onto the cart). At this time, a detachment of Germans landed in the field from armored vehicles and collaborators. The peasant persuades Fleur to hide the weapon in a heap of hay and go with him to the village under the guise of his grandson, Mitrofan.

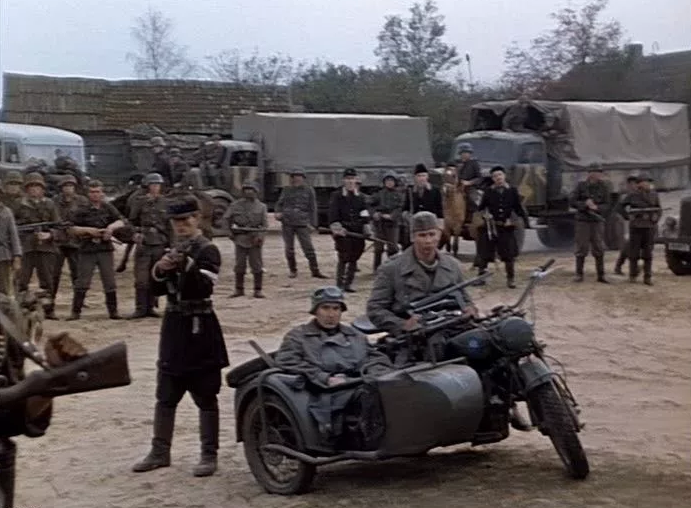

The detachment enters the village, and after “checking the documents”, the punishers, mocking and beating the locals, drive them into a large barn. An SS officer, looking into the barn, allows adults to leave without children, but no one comes out. Fleura crawls out the window, aged with fear, and behind him is a village woman with a small child. The Germans, laughing, take away the child from her and throw him through the window back into the barn, and the woman herself is dragged by the hair past the barking shepherd dogs into the truck. Continuing to rudely make fun of the locals, the Germans and collaborators pelt the barn with grenades and Molotov cocktails, listening to music, laughing and applauding themselves. Shooting the barn from different types of weapons, the punishers with the help of knapsack flamethrowers and flame. Exhausted from the horror experienced, Fleur falls, burying her face in the sand.

Waking up, Fleura goes into the forest and discovers that the executioners were ambushed by partisans. Taking his rifle into the field, he returns to the village, where he meets with his partisan detachment. There he sees a raped and severely beaten girl from a burned village. Taking a can of gasoline from an abandoned German motorcycle, the teenager goes to the place of trial of the captured punishers. The partisans are going to shoot them, but the punishers, among whom there are many collaborators, begin to make excuses and ask for mercy. Only a fanatic SS man declares through an interpreter that “not all peoples have the right to life… you should not exist.”

At a signal from Commander Fleur, he gives the German interpreter a canister of gasoline, and he, in the hope of saving himself, pours it over the screaming prisoners. But, unable to withstand the disgusting scene, one of the women begins to shoot at them from PPSh, and the rest of the partisans immediately join her. After that, a resident of the burned village throws an already useless torch into a puddle, and everyone silently disperses.

The partisans leave the village. Exhausted, gray-haired and wrinkled, Fleur finds a portrait of Hitler a little further from the court and begins to shoot at him frantically and with all his fury. The scene is accompanied by a newsreel of key events in the formation, development and consequences of German National Socialism, going in reverse chronological order: concentration camps – the beginning of World War II – the rise of the Nazis to power – the Beer Putsch and riots in the Weimar Republic – World War I, etc. Music sounds – Nazi marches and fragments from the works of Richard Wagner. Fleur shoots all this time, until an infant portrait of Hitler with his mother appears on the screen, which he does not find the strength to shoot at.

The partisans leave the village. Exhausted, gray-haired and wrinkled, Fleur finds a portrait of Hitler a little further from the court and begins to shoot at him frantically and with all his fury. The scene is accompanied by a newsreel of key events in the formation, development and consequences of German National Socialism, going in reverse chronological order: concentration camps – the beginning of World War II – the rise of the Nazis to power – the Beer Putsch and riots in the Weimar Republic – World War I, etc. Music sounds – Nazi marches and fragments from the works of Richard Wagner. Fleur shoots all this time, until an infant portrait of Hitler with his mother appears on the screen, which he does not find the strength to shoot at.

The final scene is a teenager with an old man’s face, distorted by horror and pain, and partisans leaving for a snowy forest to the music of Mozart ‘s Requiem.

Historical basis

We are obliged to exterminate the population – this is part of our mission to protect the German population. I have the right to destroy millions of people of an inferior race who multiply like worms.

— Adolf Hitler

Nazi racial doctrine included the idea that the Slavs were members of an “inferior race”, descendants of ” Aryans ” and “Asiatic races” (including the “Finnish race”), degenerated to a state of ” subhuman ” as a result of racial mixing and the influence of Asian blood. At the same time, the Russian and East Slavic peoples could be considered as the most racially degenerated among the Slavs, retaining only insignificant “drops of Aryan blood.” Nazi racial theorist Hans Günther viewed Russians as the result of a mixture of the Nordic race.with the East Baltic and with the Eastern Finns, with a strong predominance of the last two. One of the leading theorists of race studies in Nazi Germany was Egon Freiherr von Eickstedt, author of The Racial Foundations of the German People (1934). In 1938, his assistant Ilse Svidecki published under his editorship the book Racial Studies of the Ancient Slavs. The main idea of the book was that the Proto-Slavs belonged to the Nordic race, but by now the Slavs have lost the Nordic component, almost completely suppressed as a result of mixing with other races. In her opinion, the “denordization” of the Eastern Slavs is associated with the “Eastern Caucasoid” race, the type of which was transferred to them by the ancient East Finnish tribes.

Nazi racial doctrine included the idea that the Slavs were members of an “inferior race”, descendants of ” Aryans ” and “Asiatic races” (including the “Finnish race”), degenerated to a state of ” subhuman ” as a result of racial mixing and the influence of Asian blood. At the same time, the Russian and East Slavic peoples could be considered as the most racially degenerated among the Slavs, retaining only insignificant “drops of Aryan blood.” Nazi racial theorist Hans Günther viewed Russians as the result of a mixture of the Nordic race.with the East Baltic and with the Eastern Finns, with a strong predominance of the last two. One of the leading theorists of race studies in Nazi Germany was Egon Freiherr von Eickstedt, author of The Racial Foundations of the German People (1934). In 1938, his assistant Ilse Svidecki published under his editorship the book Racial Studies of the Ancient Slavs. The main idea of the book was that the Proto-Slavs belonged to the Nordic race, but by now the Slavs have lost the Nordic component, almost completely suppressed as a result of mixing with other races. In her opinion, the “denordization” of the Eastern Slavs is associated with the “Eastern Caucasoid” race, the type of which was transferred to them by the ancient East Finnish tribes.

Since 1940, the German government developed the General Plan Ost, which involved the devastation of the conquered territories in the east. The authors of the plan expected to destroy or resettle in Siberia three-quarters of the population of Belarus, and use the territory of the republic for growing necessary, but unsuitable for food plants, for example, kok-saghyz. “Instruction on Special Areas to Directive No. 21 (plan” Barbarossa “)”, “On Military Jurisdiction in the Barbarossa Region and on the Special Powers of the Troops”, “The Twelve Commandments of the Conduct of the Germans in the East and Their Treatment of the Russians”, and other directives from Hitler exempted Wehrmacht soldiers from liability for crimes and erected terror in relation to civilians. population in the rank of state policy.

According to the Khatyn memorial complex, more than 140 major punitive operations were carried out in Belarus, during which the indigenous population was destroyed, driven away to camps or for forced labor in Germany. During the three years of occupation, 2,230,000 people, that is, every fourth inhabitant, became victims of the Nazi policy of genocide and “scorched earth” in Belarus. As a result of punitive operations, 628 settlements were destroyed. Of these, 186 were never restored, since all their inhabitants were killed.

In response to the atrocities of the invaders, partisan detachments began to form. By the end of 1941, 12,000 people fought in the ranks of the partisans in 230 detachments. By the end of the war, the number of Belarusian partisans exceeded 374 thousand people. They were combined into 1255 detachments, of which 997 were part of 213 brigades and regiments, and 258 detachments acted independently.

On March 22, 1943, two platoons of the 1st company of the 118th police security battalion were ambushed by the Avenger partisan detachment. During the battle, three were killed and several punishers were wounded, including Hans Wölke. Help was called in to pursue the partisans: a part of the Dirlewanger Sonder Battalion arrived from Logoysk, and a part of the 118th Ukrainian police guard battalion arrived from the village of Pleschenitsy. Punishers shot 26 residents of the village of Kozyri, who were suspected of assisting the partisans, and on the same day broke into the village of Khatyn. After a short battle, the partisans retreated under pressure from superior enemy forces. The punishers did not pursue them, but massacred the inhabitants of Khatyn. The fire killed 149 people, including 75 children. The name of the village later became a symbol of Nazi crimes, and it was this episode of the war, according to the director of the film, Elem Klimov, that prompted him to create Come and See:

On March 22, 1943, two platoons of the 1st company of the 118th police security battalion were ambushed by the Avenger partisan detachment. During the battle, three were killed and several punishers were wounded, including Hans Wölke. Help was called in to pursue the partisans: a part of the Dirlewanger Sonder Battalion arrived from Logoysk, and a part of the 118th Ukrainian police guard battalion arrived from the village of Pleschenitsy. Punishers shot 26 residents of the village of Kozyri, who were suspected of assisting the partisans, and on the same day broke into the village of Khatyn. After a short battle, the partisans retreated under pressure from superior enemy forces. The punishers did not pursue them, but massacred the inhabitants of Khatyn. The fire killed 149 people, including 75 children. The name of the village later became a symbol of Nazi crimes, and it was this episode of the war, according to the director of the film, Elem Klimov, that prompted him to create Come and See:

I then thought: but the world does not know about Khatyn! They know about Katyn, about the execution of Polish officers. But about Belarus – no. Although there were burned more than 600 villages! And I decided to make a film about this tragedy.

Making the movie

Scenario

Originally from Stalingrad, Elem Klimov witnessed the German bombing of the city as a child. The future director was especially impressed by the night evacuation along the Volga, when, among the explosions of bombs, he saw how Stalingrad stretched for many kilometers along the coast was blazing. Strong childhood impressions from the experience remained with Klimov forever, and he considered it his duty to make a film about that period of history.

In addition to childhood memories, there were other reasons. According to the director, the ” cold war ” exerted extreme psychological pressure, and the thought of a possible outbreak of a third world war “literally felt physically.” In this regard, he personally really wanted to have time to fulfill his old dream. In addition, Klimov was dissatisfied with his previous film ” Agony “, believing that he had not coped with the task of showing the super-complex human condition, and wanted to rehabilitate himself in his own eyes.

Those who forget their past are doomed to relive it.

— Elem Klimov

Filming

In addition to live ammunition, real shells were also used in the film. This was due to Klimov’s desire for authenticity. Initially, it was planned to use pyrotechnics and explosives, but after several takes, the director and cameraman came to the conclusion that such explosions did not look natural. After that, real projectiles were used, greatly increasing the risk for the actors. For the safety of the actors and the camera crew during the filming of the scene of shelling with tracer bullets, they were behind a concrete slab 1.5 meters high and 5 meters wide.

Since a large number of non-professional actors took part in the filming, among which were elderly people, Klimov experienced severe mental discomfort, forcing them to relive the war. The director believed that, despite the fact that the Belarusians have “genocide in their genes”, the “psychological defense mechanism” – the ability of the human body to forget severe shocks – truly does not allow them to play it. In this regard, Klimov had to take unexpected steps. For example, on the set of the scene of the burning of the village, the extras – local residents – were herded into a barn, but the necessary intensity of emotions could not be achieved. Someone from the film crew started a rumor that “filmmakers can seriously burn”, and one of the actors who played the Germans fired a line from a machine gun into the air. As a result, according to Klimov, “such a human howl was heard from the barn, which could not be imitated by any actor”. In the final episode of the same scene, several people were left in the barn, who were supposed to stick out the windows and shake the gate, and as the fire flared up, exit through the back door. When they had already left, Evgeny Tilicheev, who played the collaborator translator, jokingly said that “only seven people were left in the barn”, thereby provoking a storm of emotions. With younger extras, a problem of a slightly different kind arose: many guys and girls invited to play partisans often had fun at first and were not serious about work. On the advice of Ales Adamovich, Klimov turned on wartime songs through the amplifier, which effectively set the actors in a working mood. To the detriment of authenticity, the Belarusian language had to be abandoned. According to Aleksey Kravchenko, it was decided at the dubbing “to make such a mutant of Russian and Belarusian, because if I spoke pure Belarusian, no one would understand anything.

Unfilmed scene

Subsequently, Elem Klimov, in an interview, regretted that he was unable to shoot the climactic scene of the film. At one time, it was she who aroused the objections of the censors. Boris Pavlenok, former deputy chairman of the USSR Goskino, recalled:

In the center of the picture was the fundamentally unacceptable scene “Round Battle”, where both the Germans and the partisans, crazy from blood and rage, had already lost their human appearance, turned out to be equally cruel and powerless. Willingly or unwittingly, they became equal in responsibility for the bloody action.

According to Klimov, it was because of this scene that he chose the title “Come and See.” However, the organization of the filming was far from ideal, and there was not enough time to fully implement the plan. The film was shot in chronological order, and in order to solve the director’s tasks, the lead actor, a non-professional actor, had to gradually go through the terrible path of his hero. The consistent spiritual change of Kravchenko-Flyora cost the work process an extra month and a half, and the filming “rested” in the winter: the final departure of the partisans was already being filmed in a snowy forest. However, Klimov recalled that in further conversations with Adamovich, he came to the conclusion that the audience might not have endured this scene:

This is an apocalyptic scene on a giant peat bog with a forest miraculously preserved on it, around which there is a battle of equal forces: Germans and partisans – you can’t step aside anywhere, leave, jump away, because you will fall into burning peat, like hell, and no this battle is over, the battle goes on until complete annihilation. The sun, as it were, has stopped over the forest and is waiting for people to finish each other off. And then there are civilians, and cows, and children, and the wounded – in a word, the end of the world.

Reaction and recognition

The premiere of the film “Come and See” took place in the summer of 1985 at the Moscow International Film Festival, where it was awarded the “Golden Prize” and the FIPRESCI Prize. The film was released in the Soviet film distribution on October 17, 1985 and, according to the results of 1986, took sixth place: it was watched by 29.8 million viewers. Over the next three years, the film was shown in eleven countries, mostly in Europe, but was also shown in North America and Asia. According to Klimov, the film seemed so shocking abroad that during the screenings, ambulances were on duty at the cinemas, taking away too impressionable viewers. At one of the discussions of the film, an elderly German said: “I am a Wehrmacht soldier. More than that – an officer of the Wehrmacht. I went through all of Poland, Belarus, reached Ukraine. I testify that everything told in this film is true. And the most terrible and shameful thing for me is that my children and grandchildren will see this film”.

According to a poll of readers of the Soviet Screen magazine, Come and See was recognized as the best film of 1986, and subsequently established itself in many film ratings, including foreign ones. The film holds a 97 percent “fresh” rating on the Rotten Tomatoes scale. It is ranked # 6 on Time Out magazine’s “The 50 Greatest War Movies of All Time” while also being the best World War II film. In 2008, another British magazine – Empire – included it in the list of “The 500 Greatest Films of All Time” at number 60. According to a survey conducted in 2012 by the British magazine “Sight & Sound ” among directors, it ranked 30th in the list of the best films of all time. In August 2019, the American film and television portal ” Screen Rant ” compiled a selection of the ten best films about World War II; “Come and See” took the first line in the list.

After the release of the film on the screen, Klimov for the first time got the opportunity to travel abroad, his retrospectives began to take place in different countries. The director said that, despite the incredible psychological upsurge, he began to be haunted by the feeling that he had already tried everything in the cinema. Then he returned to the idea of filming The Master and Margarita, which had previously been denied to him personally by the chairman of the State Film Committee Philip Yermash. In collaboration with his brother Herman El Klimov wrote the script based on the famous novel by Mikhail Bulgakov, but during perestroika, the director was elected chairman of the Union of Cinematographers of the USSR. For Elem Klimov, this election was a complete surprise, but he did not refuse a new role and set about restructuring the system of film production and film distribution in the Soviet Union. This activity actually put an end to his further creative plans. Thus, “Come and See” became the final film in his directorial career.

Critics

Tom Huddleston (” Time Out “, 2009), with the proviso that it is impossible to fully depict the horrors of war in the cinema, said that among the more successful attempts to do this, from “The Battle of the Somme ” to ” Saving Private Ryan “, not a single director managed to get as close to the goal as Klimov. According to the critic, this is a completely ordinary war film, “maybe a little darker”, but only until a bomb blast deafens Fleur, after which it has to collapse into the inevitable nightmare of ever-growing madness. Huddleston describes the scene of the burning of the village as one of the “most demented shots ever captured on celluloid,” the biblical massacre of the innocents.”, while admiringly noting that the make-up, which turned a ruddy teenager into a haggard old man, allows the viewer to see how the human psyche breaks, much more effectively than any book or dialogue. Alexander Shpagin, a Russian film critic and historian, used similar terms, noting that hatred and anger, elevated to an absolute, deprive people of their human appearance, and absurdist schizophrenia, which is set as a code of a work from the first minutes of screen time, continues both in actions and in the hysterical dialogues of the characters, regardless of which side they are on.

Denise Youngblood, professor of history at the University of Vermont and specialist in Soviet cultural policy, called Come and See one of the most powerful anti-war films. Unlike many Western critics, Youngblood sees the film primarily as a milestone for Soviet cinema. One of the most striking differences from the traditional Soviet military cinema of the past, Youngblood calls the absence of any heroism and embellishment: Fleura’s mother is not a noble woman who sacrifices herself for the sake of victory; children are not rosy-cheeked guys, but “children of war”; partisans are not noble heroes who talk about defending the Motherland and graciously save the lives of prisoners, and, finally, Fleur is “certainly not a hero, but just a child blindly trudging through the apocalypse”. A similar point of view is shared by Scott Tobias, a critic for The AV Club, saying that the film is “far from being a patriotic monument to Russia’s hard-won victory. On the contrary, it is a chilling reminder of what a terrible price she got”. An important component of the film, according to critic Maya Turovskaya, is the personal experiences of its creators: Adamovich’s war memories and Klimov’s personal pain from the loss of his wife.

Roger Ebert (Chicago Sun-Times) in a 2010 review called Klimov’s latest work “one of the most devastating films about the war”, where, he suggested, “the living must envy the dead.” Noting that in Soviet cinema the subject of Hitler was safe and convenient enough as a political allegory, Ebert admitted that the picture is much more than a mere allegory, and personally he has hardly seen a film that depicts human evil more ruthlessly.

cultural value

Artistic images

The film is characterized by semi-circular and circular mise -en-scenes, symbolizing the circles of hell through which the protagonist passes.

“Come and See” shows the practice of mass extermination of people, characteristic of the 20th century, as a result of which the humanist philosophical thought again asked the question about the possibilities of Good in the conditions of the total offensive of Evil. Despite the fact that the concept of extermination of people on any grounds is not new in itself, Klimov’s film covers a period of history, the memory of which remains alive in many countries of the world due to its relative recentness and the unprecedented scale of executions of civilians. The historical reality of the depicted events, emphasized in the documentary accuracy of village life, partisan household items and costumes of the film characters, complements the philosophical parable of Good and Evil, which is taken at the moment of its triumph and dominates throughout almost the entire film. Rare are short respite from the horror of war, and after them a return to torment immediately follows: rain playfully sparkling in the rays of the sun, pouring on Fleur and Glasha, quickly replaced by merciless bomb explosions; the illusory comfort of the warm hearth of Fleur’s house instantly disappears at the sight of rag dolls spread out on the floor, lying almost like corpses of people near the outskirts. As TimeOut magazine summarized: “Klimov’s film, without any omissions, states that if there is a God, then in the early 40s he took a very long lunch break”.

Having sharpened the audience’s perception with documentary accuracy, the director created the illusion of reality, saturating the imagery of the film with colorful visual metaphors symbolizing the triumph of death and the triumph of the forces of hell : quicksand stuffed with corpses; hovering in the sky like an angel of death, the horned square of a German reconnaissance aircraft ; a field covered with thick gray haze, from which, like horsemen of the Apocalypse, punishers on motorcycles with the corpse of a naked, executed man on a trailer emerge; a playful lory on the shoulder of the Sturmbannführer, casually giving the order to destroy the village. Not dwelling on obvious allegories, the director throughout the film builds characters and scenery in semicircular and circular mise -en-scenes, personifying the circles of hell that the main character goes through. One of the key here is the scene on the island, when Fleur, who has just tried to drown in liquid mud, is washed and tonsured by women, designed to cleanse the teenager before entering a new circle of hell. Only at the very end of the picture comes “redemption” in the form of white snow covering the earth, akin to white clothes that wrap the holy martyrs described in the Apocalypse.

Despite the rigid reference to a specific place and time, the film is characterized by large-scale, metaphorical generalizations. The main character does not give the impression of a person with a fine mental organization, however, his simple face and strong physique allow the viewer to associate the teenager with ordinary people, whose forces the Great Patriotic War was won. Again, the scene on the island is a metaphor designed to emphasize this idea: the protagonist feels unity with the people who are there and thus, in Klimov’s words, “carries the theme of the people.” At the same time, Fleur is the only one who emerges from a shed full of people, physically unharmed, which suggests a burden on his conscience for abandoning the villagers.

In turn, for the director, the punishers are not people, but animals, for a while and ineptly pretending to be people. Their inner motives, whether it is a sincere belief in the Fuhrer’s words or fear for one’s own life, despite a fleeting mention in the end, are not considered, although Adamovich’s story “The Punishers” described the stages of the moral decline of people selected for participation in murders from among those dying of hunger prisoners of war. In the film, the punishers are given mainly in the general and distant plans with the plasticity and behavior of infernal creatures. Nevertheless, in their mass, the killers of civilians are an important mediator of the ideas of the director, who sought to show what people can turn into when they cross the threshold of morality and morality, when the war turns into total murder and bestiality. Fleur, who finds himself in an extreme situation, as the personification of the people, demonstrates how strong a person (and a people) is who could endure such suffering.

The scene of Fleuroy shooting a portrait of Hitler in a puddle is the quintessence of the author’s thought. Shooting the emblem of violence half-submerged in a puddle – a portrait of Hitler – Fleur symbolically reverses the Nazi chronicle, while driving away the evil force, which visibly decreases in scale. Nevertheless, the last shot, at Hitler the baby, Fleur cannot fire: he did not harden and did not become like his enemies, despite everything that he experienced. Such an ending, according to critics Marina Kuznetsova and Lilia Mamatova, clearly takes the film from a hyper-realistic beginning to a traditionally realistic one, forcing the viewer to perceive Fleurin’s gesture as evidence of the hero’s inexhaustible moral strength. Literary critic Yuri Karyakin regarded this as “a great metaphor for humanism in which wisdom, nobility, overcoming, it would seem, absolutely irresistible, and, most importantly, the immediacy of a childish trusting look, which has survived in spite of everything, have merged together”. The Film Encyclopedia sums it up:

Fleura sees in front of her not a monster, but an innocent baby sitting in her mother’s arms. And Fleur lowers the rifle. Sounds like Mozart ‘s Requiem. Our eyes open to a clear sky. What’s this? Victory? Or defeat? One way or another, the last episode remains a mystery. Only one thing is certain: even the ultimate, inhuman cruelty and malice cannot destroy life in its sources.

Cinematic techniques

Stabilized with the Steadicam, the shot gives the camera the role of a cold, aloof witness to horrific.

To convey his thoughts to the viewer, Elem Klimov chose a new technique, describing it as “super-cinema”. This approach is guided by the principles of ” hyper realism ” – an excessive concentration on the details and objects of real life with a characteristic absence of the author’s emotions. The technical implementation of such a creative approach was carried out by means of the Steadicam camera stabilization system, which appeared in Soviet film production only a few years earlier and was hardly used. Despite a broken TV system provided by Belarusfilm, Rodionov captured the scenes in motion perfectly, adapting the optical viewfinder from the Soviet SK-1 camera.

Since motion photography, one of the main means of expression in modern cinema, is fraught with shaking and image vibrations, one of two sets of Steadicams purchased from Cinema Products for foreign currency was used on the set of Come and See. This device allowed cameraman Alexei Rodionov to stabilize the frame, giving the camera the role of a cold, aloof witness to horrific events. Such detached analyticity, according to screenwriter and critic Marina Drozdova, made it possible to perform radical staged tasks with cold scrupulousness. The visual radicalism demonstrated in the film was alien to the Soviet cinema of the mid-1980s, as a result of which Elem Klimov and his co-authors were blamed for the naturalistic nature of the climactic scenes. Visual techniques such as long shots and panoramic shots, combined with Denise Youngblood’s “virtuoso” soundtrack, result in the silence that follows the destruction of the village becoming “deafening”. Responding to criticism of the shock aesthetics of the film, Klimov said that the people did not forget the horrors of the war, and this memory continues to live in the genes of children and grandchildren, especially since at the time of the creation of the picture many of those who themselves experienced the events depicted were alive.

Particular attention in the film is paid to the original soundtrack, the author of which was the composer Oleg Yanchenko. The main musical instrument of the main theme is the organ, but the development of the plot is often accompanied by inexplicable noises, as well as sudden fragments of distorted music, as if played on rattling, out of tune instruments. One of the clearest examples of an unusual combination of sounds is Fleura’s temporary shell shock after a bomb explosion, when, in the perception of a deafened teenager, the distant echoes of the organ are interspersed with the ringing of bird voices and the buzz of insects, while a shrill whistle annoyingly breaks through them. Multiple layering of sounds enhances the impact of the village burning scene, when the smoke from the burning building rises to the black sky along with the desperate screams and cries of the victims to the laughter of the punishers and the roar of technology, forming a kind of “apocalyptic symphony”. When dubbing some scenes, several dozen original soundtracks were used simultaneously to create the desired effect. For example, the soundtrack that accompanies the newsreel and the shooting scene of Hitler’s portrait is “assembled” from 80 magnetic tapes with dialogues and replicas and 20 noise recordings.

Sometimes Yanchenko’s melody is mixed with well-known pieces of music (for example, ” On the beautiful blue Danube ” by Johann Strauss). Documentary footage in the finale is accompanied by Ride of the Valkyries by Richard Wagner, while Glasha dances to the music from Grigory Alexandrov ‘s film Circus. The film ends with Mozart’s Requiem, about which Roger Ebert wrote the following lines:

Is it true that the audience is demanding some kind of release or catharsis ? That we cannot accept a film that leaves us without hope? That we are trying to find spiritual uplift in the quagmire of malice? There is a curious scene in the woods, with the sun falling through the leaves, when the soundtrack, hitherto somber and mournful, is suddenly released into Mozart. What does this mean? I think it’s a fantasy, but not Fleur, who probably never heard such music. Mozart condescends into the film as a deus ex machina to lift us out of his despair. We can accept it if we want, but it won’t change anything. It’s like an ironic mockery.

Meaning

According to Alexander Shpagin, Klimov made a “jump up” with his film when he collected common motifs and cliches of Soviet military cinema and “brought them into the metaphysical perspective of Hell.” Shpagin believes that Klimov “closed the theme of the war in Russian cinema for almost fifteen years”: the next significant works, in his opinion, were “Cuckoo” and ” Own “. The picture also influenced the recognized masters of directing. The effect of “deafness” and ringing in the ears experienced by Fleura after a nearby explosion was used by Steven Spielberg in the military drama Saving Private Ryan. The German magazine “Ikonen” also noted the influence of the tape on the later work of director Terrence Malick. Oscar- winning British cinematographer Anthony Dod Mantle considers Alexei Rodionov’s cinematography in the film to be the greatest in history, noting in particular the mastery of staging the final scenes.

In 2001, the film was released on DVD by RUSCICO in a two-disc edition with additional materials. The dvdreview.com criticized the publication for poor image quality, noting washed out colors and digital noise.. The audio track on the DVD received more praise, but still showed certain flaws. For example, the weakness of the sound design of the dialogues is indicated (when viewing, the sound comes from all the speakers at once, nullifying the advantages of a stereo sound system). The positive aspect of the DVD, the reviewers called the presence of additional materials, which include interviews with Elem Klimov, Alexei Kravchenko and the artist Viktor Petrov. Additional attachments on the disc include two documentaries “Partisans in Belarus” and “Atrocities of the Nazis”, which clearly demonstrate the harsh realities of the Eastern Front. Summarizing the feedback, the site’s editors gave RUSCICO low marks for the technical implementation of the DVD, but favorably commented on the very fact of releasing the picture in digital format, since some technical shortcomings are successfully compensated by the “power” of the film itself.